Development of the Financial Inclusion Innovation Lab in Pakistan

Several supply-side digital payments and banking developments have taken place in Pakistan in the last 5-7 years, led by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP), and development finance institutions such as Karandaaz Pakistan (funded by the Foundation) and the World Bank.

Key market developments include the development and launch of an instant payment scheme (Raast) with one trillion P2P transactions in 11 months generated from more than 20 million Raast IDs, multiple G2P use cases linked with Raast, including government salaries processed via Raast, and other G2P payments in the pipeline such as disbursement of seven million monthly social safety net payments to women from the bottom of the pyramid from Benazir Income Support Program. In government, the digitalization of the Central Directorate of National Savings program with more than four million savers has linked around one million saving accounts with the digital financial ecosystem for ATM and payment interoperability. In addition, a USSD-based interoperable scheme (Asaan mobile scheme) has enabled more than five million non-smartphone users to open and operate branchless bank accounts. Furthermore, the SBP has issued multiple licenses to promote digital financial services. The categories of licenses include issuance of no objection certificates (NOC) to five Digital Retail Banks (DRB) , twelve Electronic Money Institutions (EMI) four gone live, twelve Payment System Operators/Providers (PSO/P) – five gone live, and eleven branchless banks-all live. In addition to issuing licenses, the SBP issued regulations enabling digitalzing financial services, including Digital Onboarding Framework for Consumers enabling remote account opening using digital KYC, Digital Onboarding Framework for Merchants, and a framework for banks to outsource to cloud services providers.

In addition, the country has also witnessed a substantial rise in the number of Fintech startups focusing on payments, savings, and lending use cases. Many other startups are digitally disrupting e-commerce, e-education, telehealth, retail order fulfillment, and ride-hailing verticals. These developments have led to an increase in digital financial accounts and transactions over time. The SBP reported eighty-five million Branchless Bank accounts till June 2022 out of which forty three million are active.

A sizable investment has been made in digital finance, including corporate houses and venture capital investing in startups. Karandaaz Pakistan, funded by the Foundation, provided grants along with USAID.

What Makes Digital Miles Different?

What makes Digital Miles different?

Digital Miles takes inspiration from solving ‘last-mile’ issues, or in essence, digitalizing the last mile in a customer-centric manner

Similarly, financial institutions have started focusing on solving SME lending issues, a vast gap in Pakistan, especially for small companies. The Securities and Exchange Commission has granted twenty-one licenses to provide Investment Financial Services (IFS) licenses and issued regulations and policies enabling digital finance, including warehouse receipts Secured Transaction Registry and framework for Non-Banking Financial Companies engaged in digital lending.

Emerging Gap

While the results of all these efforts have started to appear, and financial inclusion has increased from 14% in 2017 to 30% in 2022, the gender gap has increased from 13% in 2017 to 16% in 2022. Similarly, there is a 10% Rural-Urban gap in financial inclusion.

Key reasons for the 70% excluded population are: do not know what mobile money is used for, do not know how to use a mobile wallet, and prefer to pay cash.

The main reason for still lagging and excluded segments is that most private sector digital financial services providers focus on the banked. At the same time, the unbanked are generalized as a population who do not want to get ‘documented’ and hence are reluctant to adopt digital means. The fact is, on the contrary. The unbanked population wants to use digital means; however, the current value propositions do not meet their needs. Furthermore, it is a researched fact that digital developments marginalize people with low literacy as their confidence in using digitally enabled solutions is extremely low initially, and the fear of making a mistake is a significant barrier to adoption. Hence these segments, primarily rural but also present in urban areas (especially the migrant workers), remain committed to old proven mechanisms and habits of using cash.

There has been little effort to develop solutions based on real-life profiles of these segments. A glaring example includes women, who are getting further marginalized as most FSPs, including fintech, consider all women of the same profile, resulting in a very low uptake of DFS among women. Social barriers and norms add to the issues of adoption among women. Another example is youth. High-level interaction with multiple universities and college-going students reveals that youth, even being digitally savvy and having mobile accounts, end up using cash since the FSPs are not focused or unable to develop youth-centric use cases. Lower revenue merchants (mom & pop shops) are another category where merchant acquirers rely on card-based discount rate models. This results in merchants resisting adopting digital payments as they see no real value in adding costs to their business without seeing an upside.

In summary, while we have many supply-side platforms set up, the approach for the ‘last mile’, or where the rubber meets the road, is predominantly non-customer-centric. The FSPs deploy a usual sales and distribution approach of deploying existing products with minor tweaks to the unbanked segments. Similarly, initiatives for market development that require patience and new approaches or collaboration with other suppliers and sometimes competitors do not go forward. The innovation in financial services remains within banked, and the service does not extend to the unbanked, who then rely on existing informal banking and cash mechanisms.

Digital Miles-A Financial Inclusion Innovation Lab

With the above background and the number of developments that have taken place in the last six years, there is an opportunity to create a dedicated Financial Inclusion Innovation Lab (FII Lab) to develop solutions and business models for converting the specific segments of unbanked to banked. The FII Lab will leverage the existing national digital infrastructure and develop solutions for the customers that solve their particular constraints and help transition them from unbanked to banked.

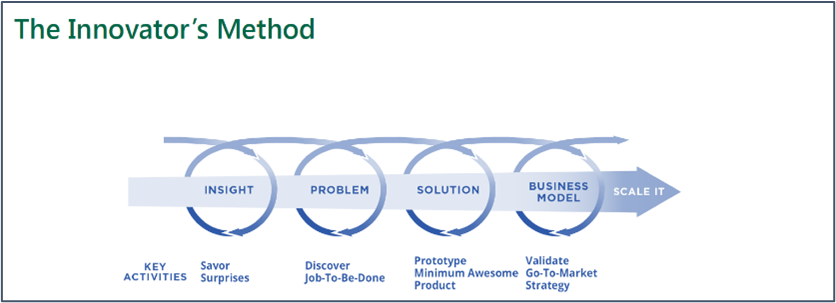

The FII Lab will utilize a human-centered design approach, identifying the issues and challenges faced at the “last mile” of the target segments, creating collaborations with on-ground suppliers locally present, and building local propositions. In addition, the FII Lab will specifically deploy Innovator’s method to develop solutions, and business models for the unbanked financial services use case. While appearing simple and intuitive, financial institutions do not follow the Innovator’s method. Business and product managers usually start with business models as a given and develop solutions that support existing models, reducing innovation scope. Digital Miles would implement the Innovator’s method to design solutions that may require creating a new business model that may not be present in the current digital financial services providers. After prototyping a minimum awesome product to solve a relevant problem that target segments have, Digital Miles would also endeavor to develop business models to scale the product.

Target Segments

The target use cases are divided into three main categories:

|

Category |

Key Challenges |

|

Digital Finance for the ‘Low-literate’ segment |

Pakistan, unfortunately, has a large segment of low-literate people. An innovative approach of ‘dumbing down’ technology is required to provide DFS in an extremely intuitive manner. |

|

Segments with extremely low financial inclusion yet economically active |

Mom & Pops shops do not want to use digital acceptance as they see no upside in using digital finance over cash University and college-going youth require DFS solutions that address their social needs and are not impressed with current basic financial applications Women – both homemakers and self-employed– the biggest segment that saves; digital finance needs to provide potent solutions to their needs Domestic migrant workers rely heavily on agents to send money back home, which is cash out for use. Solutions are needed so that money back home is used digitally and not cashed out. |

|

Rural segments

|

Farmers who are part of the rural economy have to rely on cash to purchase inputs and sell their crops. As a result, the markets and ecosystem are cash dominant and ripe for digital finance innovation. |

Connect with the Team Now!

Drop a Comment

Connect with the Team Now!

Drop a Comment